Dustin Whitney, BS, Michael Szarek, PhD, MS, Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD

While it is true that the global population has tripled since 1950, doomsday predictions of overpopulation are misleading and could be based on flawed interpretation of widely propagated demographic statistics. Problems may arise when policies are based in potentially flawed analyses, which became apparent when the United Nations (UN) added a new statistical variant to their 2017 population report.

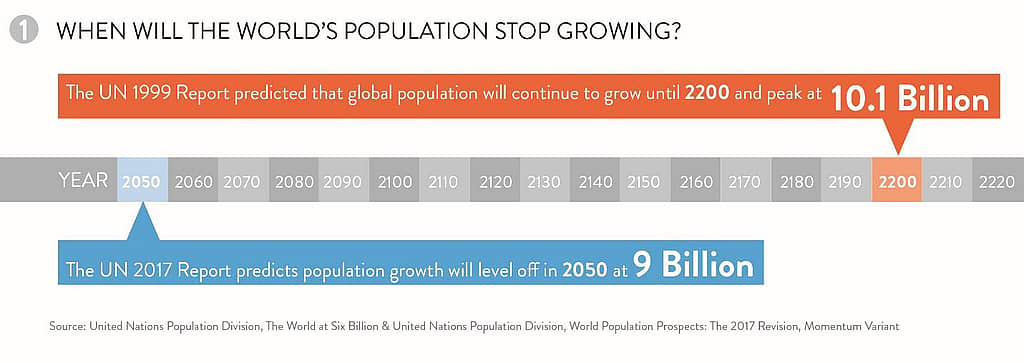

Since the 1950’s, the UN Population Division has published biennial reports on global demographic metrics and trends. In 1999, the UN published “The World at Six Billion”, suggesting that the world population would reach 10 billion before stabilizing in the year 2200.

The UN is the foremost authority on the topic of global demographics. In fact, virtually all analyses performed by governments, economists and major investment operations associated with numbers of people, their geographic regions, and ages are based upon UN’s reports. The U.S. government entitlement and pension trajectories, the balance of economic power—as determined by the World Ban —and virtually all major public and private spending programs use the same numbers, distributed by the United Nations.

Due to process refinements and better data quality and availability, the UN’s population projections have been reasonably accurate at a macro level. Anyone who has performed some basic projections, though, understands that the interpretation of demographics requires a mixture of art with science. Who could have predicted the paths of refugees fleeing from countries in conflict or the devastating effects of HIV/AIDS, for example, on global demographics?

A deeper analysis of the UN reports reveals some missteps. The impact of basic health improvements and modern medicine, for example, was greatly underestimated. The 1999 UN report declared remarkable life expectancy increases of 20 years since 1950, predicting that people would live until the age of 76 by 2050. Yet, this lifespan is already realized today in all but the lowest of income countries. However, the UN’s biennial population reports have over time been consistently lowering the average number of children whom women bear in their lifetimes. When the numbers are compiled, these types of miscalculations tend to cancel each other out. Thus, the errors of predicting too many deaths have been offset by the errors of predicting too many births. The world population has grown not so much because more babies are being born, but because fewer people are dying.

Recognizing the fertility and mortality trends, in their 2017 revision report, the UN introduced a new momentum variant “to illustrate the impact of age structure on long-term population change.” When momentum is considered, the outlook is noticeably different than previous predictions, and may introduce a much different narrative. Global population could stabilize as early as 2050, reaching approximately 9 billion people—150 years sooner than projected in the 1999 report and at a level of 1 billion fewer people.

This may be welcome news to those concerned about global overpopulation and the world’s limited resources. The topic is much more complex, though, than simply changing the rate of global growth. These population shifts could mean serious changes for the global workforce, as well as education and healthcare considerations. The number of people who can participate in the workforce vs. those who have aged out is becoming increasingly out of balance. We are just beginning to feel this impact.

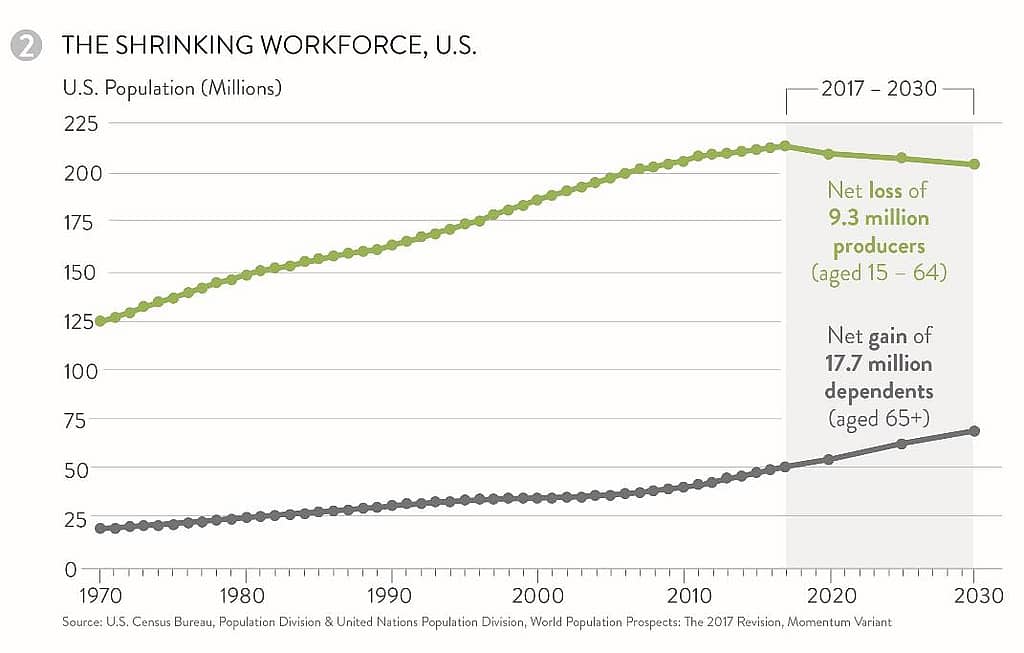

We are three years into a 13-year period of a major demographic shift. By 2030, the projected amount of people working age individuals (15-64 years) in America will be 204.5 million which is >15 million fewer than the 220 million projected in the 2000 UN report and is >9.3 million fewer than current levels. Twenty years ago, the UN projected a 3% workforce gain of 6 million people, but instead we are now facing a 4.4% workforce decline of >9.3 million people. According to the 2017 US Census Bureau figures, America will lose >700,000 workers annually between now and 2030. That’s 2,000 workers every day. Over the same period, almost 18 million more people will be >65 years old. That’s 1.4 million annually, or 3,700 per day.

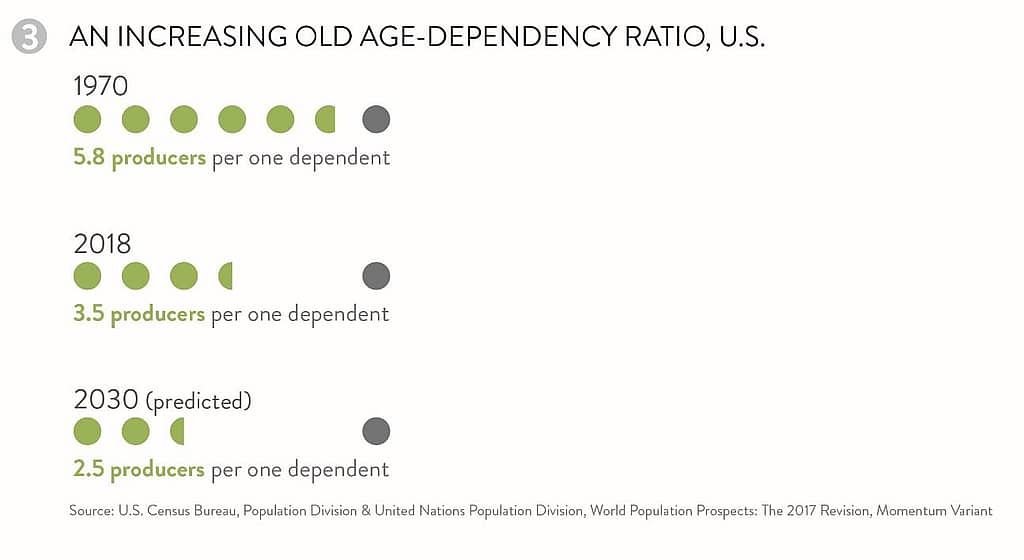

Economically healthy societies require balance between age cohorts. Those who are too old to provide for or take care of themselves rely on those who can work and support programs to provide life’s needs. Those working will eventually grow old, “age out” of the workforce, and rely on those in younger cohorts to backfill their roles. According to the US Census Bureau, there were approximately six people of working age for every one person >65 years in 1970. In 2018, that number was 3.5. By 2030, there will be only 2.5 people of working age to support every person >65 years. The fundamental composition of the population is shifting. The numbers tell us a worrisome story.

These numbers will likely become even more dramatic in future UN reports as they continue to chase fertility and mortality changes. US Fertility has not been at replacement rate (2.1 children per woman) since the early 1970’s—it was 1.87 during the five-year period between 2010 to 2015 and 1.7 in 2019. Advancements in medicine are likely to continue to improve life expectancy into the future, and we will need to provide care for this aging population without the replacement younger generation for the first time.

These demographic shifts are going to present tremendous challenges for business and society. We need to re-evaluate the fundamental components of our economic systems and rethink our approaches to infrastructure, community development, and healthcare systems. Prospects of automation, the use of robotics and deep learning machines are not threats, but potentially important solutions. Likewise, today’s immigration debates are not merely matters of humanity and justice, but of economics and of future prosperity.

About the Authors:

Valentín Fuster is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), past President of the American Heart Association, past President of the World Heart Federation, and has been a member of the US National Academy of Medicine. In the United States, Fuster serves as Director of Mount Sinai Heart and Physician-in-Chief of The Mount Sinai Hospital. In his native Spain, he serves as the General Director of the National Centre for Cardiovascular Research (CNIC) in Madrid, and also chairs an international project, the SHE Foundation (Science for Health and Education).

Michael Szarek, PhD, is a Professor and Chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, School of Public Health. Dr. Szarek also currently serves as Associate Dean for Research Administration. He received his MS degree in biostatistics from Harvard School of Public Health and his PhD in biostatistics from New York University.

Dustin Whitney is the founder of the Whitney Group, a business formation and research organization. Dustin’s career has been spent growing and developing entrepreneurial companies. Current projects include the future of labor, automation, and the key cultural challenges associated with them.